MAURICE

Maurice is an old man – he will soon turn 89.

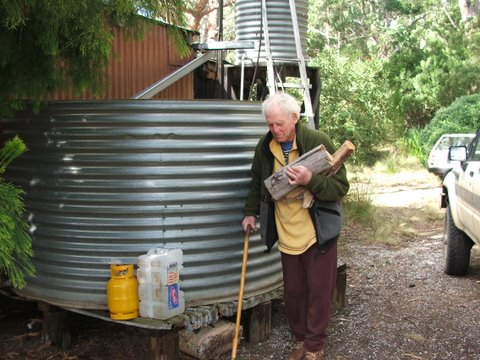

He has the slow stooped walk of the very old. His skin is smooth and clear with deep, furrowed lines around his mouth. Bright, astute eyes weep with evidence of recent surgery. He limps, holding a cane, heavily favouring his left leg. But his wit is as sharp as ever, he still has thick, curly hair and his eyes sparkle with a lively intelligence that will never age.

Maurice has had many homes but his heart lies at Cloudy Bay lagoon on South Bruny Island.

“It has a different feel about it… when I get there I feel as if I’m home,” he says in his slow gentle drawl.

The land has been in his family since his grandfather’s brother bought it 150 years ago. Parts were sold off over the generations, until Maurice inherited ten acres. Hardships forced him to sell some and he now has a one-fifth share. Two acres is all that remains of the 164 acres Alfred Conley originally purchased, but the family name will be there for generations – Maurice’s land is at Conleys Point.

Getting to Cloudy is an adventure. First, the ferry – fun, cold and wet. Then a long drive down the island: over the neck where penguins roost and beaches look magnificent; down the dirt roads where timber houses sit, forever timeless; past the shop where Tim Tams cost a fortune but hot chips are darn good; all the way to a locked gate that accesses miles of undulating paddocks.

As you approach, the scrub crowds in. Wattles and bottlebrushes spring up over the track and recent clearing for vehicle access is evident. It regularly requires a chainsaw and brush-cutter just to get there. The car rollicks up and down sand bumps and the growth is so close it scratches the roof. It feels like an eternity down the bush track, but it’s only about ten minutes. Then you’re there. You see the lagoon looking flat, still and glorious.

It’s December in Tassie and the weather is superb.

Maurice’s old one-room shack with its enormous, ancient fireplace, hides behind the scrub. Nearby are all his creations: a pyramid; a windmill to power radio and lights; outbuildings and sheds; a vast flue suspended over an enormous camp fire; sheltered bench seating for 20 and a couple of dinghies. There are woodpiles, water tanks and old cars everywhere. Birds trill, a black snake hides under corrugated iron by the creek and there are no humans in sight. It’s another dimension.

Maurice James Conley was born on a wild, stormy night, 24 November 1917, on the Wainui trading vessel, travelling between Strahan and Hobart. His parents, Athol and Amy, were travelling in her heavily pregnant state to relocate from Queenstown to Bruny Island.

Arriving on Bruny with two small children, Athol acquired a timber mill and built a home for his growing family out of scrap timber. They moved in with only four rooms, eventually expanding to five bedrooms living areas and plenty of outbuildings. There was also a large front room that Athol joked he would never finish before the family left.

“The big front lounge room was never lived in ‘cause he never quite finished ‘til we all left home, so it’s where we kept all the spare socks,” chuckles Maurice.

The five-bedroom house was home to Amy, Athol, their seven sons and extended family. In the early years, Maurice shared a bed with two brothers. Being the middle child, he had the middle spot in the big double bed. When it dipped in the centre, the brothers would roll in and stifle him with the closeness.

At the age of six, each boy started chores. They’d collect kindling, bring cows in for milking, separate the cream, pick strawberries and assist in butchering calves.

“I had to hold the animals, which I’d cry all night about when I was a little kid, and hold it while they butchered it… He hit ‘em in the head with an axe and cut their throat, and then you hold a bucket underneath to catch the blood.”

At six, Maurice also started at Lunawanna Primary School. A competent student with a talent for mathematics, he finished primary school then attended Hobart Technical College in 1930. Soon after however, the Depression hit and Maurice had to leave school at 13, as they could no longer afford 12 shillings a week board.

Maurice returned to assist his father in the family sawmill. His first paid work came when Athol won a contract to repair roads. The contract was worth 14 pounds – a small fortune at the time. The money covered equipment and wages for three men. The 14 pounds from the council was the only income they received that year.

Maurice wheeled sawdust at Clennett’s sawmill for two years before getting a job at 15 driving steam logging locomotives.

“That’s why my back’s like it is today. I got caught up in the timing shaft. Completely stripped off all my winter gear from end to end in two seconds. The timing coupling just caught and then all my winter clothes, my flannel underpants, completely stripped and took the socks out of my boots. Everything was gone. All I had left on was the tape off a singlet ‘round my neck… My back’s like a shelly beach where the coupling went up and down and ground in my back and all my hip… There was a bloke there and an old motorbike, he drove me home to get some more clothes. It was half past four in the afternoon, [the boss] said when he goes home to get clothes on he better have the rest of the afternoon off’… If it could have spun me I would have been mincemeat but it couldn’t spin me because of the wood box.”

Another accident years later left Maurice with a broken neck. Living back on Bruny in 1970 – after his marriage ended and an electrical fire burned his block of units down – Maurice tripped in long grass, fell over a retaining wall and crashed head first into a concrete veranda. By hell did it hurt. The first medical help came from the local nurse, who inexplicably dragged him around for hours attempting to make him walk. They airlifted him to the Austin Hospital in Melbourne for intensive treatment. Maurice was unable to move anything but his tongue for the first few months.

“So you’d have to think of nothing. We had a pegboard ceiling – a huge, big pegboard ceiling. So I’d count the holes in the pegboard ceiling: corner-to-corner, crossways and every way… Interesting life that was, ‘cause you couldn’t move. Just look up.”

Maurice was never expected to walk again. When he finally recovered, he told the doctors, “This is a miracle. You cured me,” But they simply said, “We done nothing for you. We don’t know how – you should never come outa that.”

Recovering from a broken spine isn’t the first miracle Maurice believes in. His family were Catholics – considered ‘religious hypocrites’ in the community.

“I know the time when my grandfather was dying and the good Catholics were down there and they thought he had hours to live so [the priest] came straight to the house and came in to do the last rites… He come to, out of his unconsciousness and said, ‘get that bastard out of this bloody house’ and he lived another 20 years. So the priest cured him.”

Maurice also remembers a much-cherished aunt, sent home to die after a cart accident, who cured herself through faith in Christian Science and lived another 40 years. But his faith was shattered when he and his wife took in a four-year old child, who died from stomach cancer three months later.

“Her name was Lisa and while there, she was like a little angel. She got cancer and died the most terrible agonising death that I ever seen. Standing up in hospital screaming in intense pain, and I switched back to Christian Science in desperation – the last hope. I stood back and watched and it didn’t work and I lost all faith… Everybody at the last looks for something that probably doesn’t exist. You’d’ only do it in desperation.”

Despite times of pain and grief, Maurice also remembers the happy years. Married for 35 years to his childhood sweetheart, June, they were the love story of Bruny Island. Unfamiliar and shy around girls, he first saw her stepping off the ferry and thought she was a bit of alright. They married in 1941, after Maurice enlisted in the army, fearing he might go to war. He had little to fear – his father had one son fighting in England and another recently enlisted, so Athol begged that one be discharged – they tossed a coin and Maurice won. Reg went to war, was wounded and then captured in Timor. While on a Japanese hospital ship en route to Burma, he died when an American submarine sank the ship.

Parenthood soon followed married bliss. Carol, their first-born child, arrived in 1944, followed 18 months later by David. Having children was a life-changing experience.

“It tied your nose to the grindstone a little bit tighter and I suppose [gave you] a reason for existence… They were both big kids and I’d pick the two of them up and carry them about three-quarter mile ‘round the road up to mum and dad’s place. I was that proud of me kids you see. Like all parents.”

Reflecting on his life, Maurice declares proudly,

“I can’t think of anything I’ve done I’m bloody ashamed of. Not even some of the hellish things I’ve done. Even though at the Bruny pub I got called a drunken so-and-so and a bloody murderer. Didn’t worry me in the slightest because I knew that I wasn’t.”

A curious statement, which perhaps relates to a car accident he was involved in, resulting in the deaths of two motorcyclists.

Maurice says he never drank to excess, but relatives disagree. He became estranged from his family after having an affair with a tenant in his unit block, though the relationship ended during his convalescence in hospital. Dates and facts become confused and shadowy as Maurice refuses to acknowledge any affairs and family members lost contact once they considered him a drunk and a shameless womaniser. He is the last surviving son of Athol and Amy’s seven-son brood. There are few people left to confirm where the truth lies. But one thing is certain – Maurice is fiercely proud and headstrong and, in his declining years, he chooses to focus on the good, not the bad.

He would like to live permanently at Cloudy Bay but access is difficult. He divides his time between Cloudy and Kingston, where he is involved in a 23-year liaison with a woman 32-years his junior. It is a volatile relationship – fuelled with drinking binges. Cloudy Bay is his refuge. He spends weeks there alone. When at Cloudy, Maurice never drinks.

He reflects on life, listens to the cricket, tinkers in his sheds and spends time in the bird sanctuary he created.

He built his shack around a huge fireplace – the only remnant of the old family shack, burned down years ago. Maurice, with friends and family, carted in every plank of wood, piece of tin and nail, by boat, truck and on foot. He constructed everything he requires to lead the simple, peaceful life he loves. The fireplace has water pipes running through to heat water for the shower. It’s so effective you have to cool it down to bathe. There’s a huge bed adjacent to the fire. Opposite, are a couch and desk, and in front of the hearth are two ancient armchairs. Behind is the kitchenette – graced by benches, cupboards and a sink running only cold water. Out front is a protected storage area for valuables. Paintings and photos of his beloved children and grandchildren line the wood-panelled walls. Letters from loved ones and collections of photos fill the drawers. Maurice’s heart and soul are embedded into the foundations of his shack. The only place he truly feels at home.

Relatives remember Maurice as a ladies’ man and a heavy drinker. A man who drank vodka at work and threw away his marriage with affairs. A man who was argumentative and foolish when on a drinking binge and easily seduced by women all his life.

The man I see is an old man – stooped and frail, proud of who he is. A man who filed down old Ford piston rings to fit an old Ronaldson Tippett water pump and designed a swivel shelf for his television when television first arrived. A man who cannot tolerate idleness and loves mental arithmetic. A man who some relatives describe as handsome, smart and charming.

He is my grandfather – largely estranged from the family, I barely remember him at all. Now that I have my own family, I feel a need to reconnect and to give my children the gift of extended family. And he is thrilled to get to know us.

Maurice passed away in July 2012, aged 94.

I wrote this feature article in 2006 as part of my journalism degree. Please remember I was a student at the time! It is also Maurice’s story as told to me by him. I fear he may have glossed over – and even lied about – a few incidents in his life! But I hope it captures the spirit of the man never-the-less.